I think a lot about Disney movies - if that wasn't abundantly obvious from previous blog posts, like where I ranked Every Best Animated Feature Winning Film - but more than that, I think a lot about the source material these movies were based on. Overwhelmingly, Disney films adapt well-known stories, such as fairy tales, often stamping them with such a general sense of Disney-ness, that they become the de facto versions of those stories in our heads.

For example, what animals do you first picture when you think of Cinderella getting help?

Is it mice?

Because in the Brother's Grimm version, it's doves who serve as her friends and guardians. Cinderella, in fairness, is a very popular story structure, with countless versions around the world and an array of animals that help her. But that's the thing - it could have been fish or lizards as easily as mice, yet Jacques and Gus-Gus are the ones that jump to mind for anyone raised on Disney films.

|

| I like to imagine this is a Marvel movie and in a post-credits scene, Cinderella asks the bluebirds to please peck out her step-sister's eyes. For the Grimm Brother's purists! Real fans KNOW! |

But it's not just the fairy tales Disney has used to build its collection of classic movies. Everything from Bambi, to The Aristocats, to Pocahontas has some children's book, short story collection, or grievous misunderstanding of American history to pull inspiration from. The first full-length Disney film that could be considered an "original" story is probably The Lion King. I'm inclined to say the development of that movie was too chaotic for it to be thought of as actually "based" on Hamlet (frankly, they could have saved themselves years of trouble if it was), but the studio did gradually note the similarities as the film came together. For those keeping score, that's thirty-one Disney movies before anyone bothered trying to write an original screenplay. And it was several MORE years before anyone wrote anything original, good and not resembling Shakespeare - Lilo and Stitch, Disney's 42nd feature-length animated film. That movie's a trailblazer, man.

Granted, not all Disney movies are based on fairy tales. In fact, there's a very enjoyable film called Saving Mr. Banks about the rather arduous journey Walt Disney had to go down in order to convince author P. L. Travers to sell the film rights to her beloved children's books, the Mary Poppins series, to his studio. Disney used to purchase the rights to contemporary novels frequently, including 101 Dalmatians and The Rescuers among their adapted works. I wouldn't mind seeing them try their hands at animating recent books again. If nothing else, I would love to see them do the Prydain Chronicles justice. The books are super charming, but Disney's The Black Cauldron is (unfortunately) a mess.

|

| Still love the design of this poster. |

For the majority of their output, however, their animation has focused on older stories. Once copyright expires on a creative work, it enters what is known as the public domain, where no one entity can make legal or monetary claim on the use of a particular work. Copyright laws vary widely around the globe, but they generally protect a work from unlicensed use for some length of time from either the publication date or the author's death. This way, the author of a work enjoys the right to fiscally benefit from that project during their lifetime and has some creative control over how the work is presented to the public. Overall, copyright is a good thing that protects the livelihoods of working artists, but there is something special about the stories in the public domain. Because when a story is old enough to go into the public domain it belongs to everyone.

There have been so many versions of Robin Hood over the years, and it's not just because it's a beloved folk tale. It's because legally, there can be. Ever wondered why Jane Austen remains so popular with people today? Well... there aren't a lot of other famous romantic comedies that absolutely any artist can riff on and then sell their version without paying royalties to someone's estate. Disney gradually became incredibly good at taking these well-known stories and reshaping them for animated film. So good, the techniques they used could be their own blog post. (Foreshadowing?) I think particularly of the Disney Renaissance, when Disney really pivoted away from using copyrighted characters, like they had in earlier decades, and focused instead on their classic fairy tale roots.

Disney is not in the habit of having original ideas. Well, they do so MORE often now, but... is that actually for the better? A good number of their "original" stories are among the most underwhelming Disney movies. Brother Bear and Raya and the Last Dragon are not awful, but I can't shake the feeling they would both be better if they were based on actual indigenous stories rather than a rough smooshing together of various cultural traditions. The best films to come out of the "original story era" like Moana and Encanto might not be pulling from specific stories, but they do at least have much more specific points of inspiration. For instance, Moana teams up with Maui! An actual legendary figure! Arguably, it is still an adaptation, in the same vein of Hercules a generation earlier. (Encanto is a unicorn of a film, but as mentioned, it is specific. It's set in Colombia and doesn't shy away from referencing the country's history with civil war.)

But the bedrock of the Disney brand - one of their most underrated skills - is adaptation. And I cannot overstate how much I freakin' love a good adaptation. Adapting a story across genre of media and generations is an artform, that might make you look like an idiot when it's botched (what moron thought James Franco should play the Wizard of Oz???) but when it's done right, it's just so satisfying. (Oh my heart! Glinda and Elphaba used to be friends!)

|

| They're only angry because they love each other! (insert crying emoji) |

One advantage of adaptation is that it invites the audience to compare various versions of the same story and let them speak in conversation with each other. Wicked, for instance, uses The Wizard of Oz as a jumping off point for the superficiality of how evil is often perceived. In a story where "evil" was seemingly baked into Elphaba's skin color and very name (The Wicked Witch of the West), what hope did she ever have of people treating her otherwise? That kind of barebones morality is a reoccurring feature (problem?) in children's literature, with The Wizard of Oz being just being one of the more blatant examples.

But as in Wicked, in real life, the villain might just be the Wizard himself. Sometimes the person ruining everything for everyone is the seemingly friendly, great and powerful entity that provided you with your first entry point into the story. Sometimes, an over-long Wizard of Oz metaphor turns out to be a segway into me complaining about how public domain law changed in the 70s and went from protecting artists, to just making life difficult for everyone.

The Wizard is Disney. Disney is the bad guy. Wow, what a twist.

Copyright Run Amok

I keep mentioning The Wizard of Oz, because it's one of the oldest classic books currently in the public domain. The series of books, published from 1900 - 1920, began dribbling into public domain over the 20th century, as US congress passed numerous Copyright Act amendments that slowed the release of the full series (and all other intellectual property) into the public domain. You can actually track the progress of The Wizard of Oz series into the public domain based on the release dates of various derivative works. Like, did your childhood have a day that was traumatized by the 1985 film, Return to Oz, "sequel" to the MGM musical classic? Well, you can thank the fact that Disney was trying to cash in on the rights before the copyright (which they had purchased) expired. And then there's Wicked - not the musical, but the novel it was based on. It came out in the 90s, after most of the Oz material was finally free to use. I like to picture Gregory Maguire writing Tik-Tok into the background of one scene, then raising a fist skyward and shouting "NO ONE CAN STOP ME!!!!"

|

| Tik-Tok. Real fans KNOW! |

As mentioned earlier, copyright laws vary worldwide, with the United States having some of the most stringent laws. Being the capitalist giant it is, this effectively means that if anyone wants to adapt anything for free and distribute it in English, it's gotta be in the US public domain. Unfortunately, the US public domain was effectively frozen for decades thanks to none other than Disney. Yes, those great abusers of the public domain themselves - master adapters of Sleeping Beauty, Aladdin, and Mulan - joined a few other media megacorps and Sonny Bono (unexpected villain twist!) in lobbying the US government to extend copyright protection for an obscene amount of time, and that's why The Wizard of Oz and it's sequels spent years as the newest, shiniest story anyone could take a shot at adapting.

At this point, US copyright for works published before 1978 is 95 years. The thing is, while I'm all for copyright protecting a creator's right to profit from their work, 95 years is a freakin' long time. At the turn of the century twentieth, copyright laws averaged around 25-50 years. 50 years seems like a perfectly reasonable extension to me, since it's effectively the length of one's "working life" in North America. During that time, creators should have the ability to profit off their works, control their distribution, and create whatever other derivative works they want. But beyond that, I kinda don't see the point.

50 years later, it won't be the original creators making work based on these classic stories, but someone else. In other words, extensions like these really only benefit corporations, not people. They gatekeep works so that only certain people get to adapt stories - the ones with pockets deep enough to pay for rights. This is why any time Sony and Disney fight with each other over how to divvy up profits from Spiderman movies, I can NEVER root for Disney. Spidey would be in the public domain by now, if Disney hadn't lobbied so hard to avoid ever letting anyone but them legally use Mickey Mouse. Sure, Sony is also a soulless megacorp and probably supported the Sonny Bono (booooo!) laws too, but hey. They're not the villain-protagonist of this story.

|

| Just think. With better laws, we could ALL make our own Spiderman. Though some fear that would be... too many spidermen. |

Return of the Public Domain

Thankfully, mercifully, those protections are finally beginning to expire and stories are getting added again, as the prescribed time elapses. Yes, it is finally more than 95 years since the 1920s. We now have culturally relevant, modern icons like flappers, suffragists and pre-depression era venture capitalists to relate to. So current!

In all seriousness though, I am grateful. Wonderful, classic stories get added each year and one of my favourite traditions is checking the list of what's entered the public domain in January. And sure enough, as famous stories begin to drop into public domain, new adaptations are taking off as well. The big news of late has been Blood and Honey, a slasher film centered on............ Winnie the Pooh. Huh.

Look, I don't plan on seeing that film, but I am honestly THRILLED that something like this can exist now. I want it all. The weird stuff, the goofy stuff, the scary stuff, the pretentions high-brow stuff. I want us to be able to engage with and easily adapt the stories of the past. Because you never know, right? You never know what creative people are going to do when they finally get their hands on stories we love. For instance, right now Florence Welch is spearheading a Broadway musical version of The Great Gatsby and there's some serious Wicked or - dare I hope - Hadestown upside with a project like that. And now that the butt-munchers holding the copyright to the last Sherlock Holmes short story collection can no longer litigate people within an inch of their life, we might get more indie creators trying their hands at adapting the world's most famous detective.

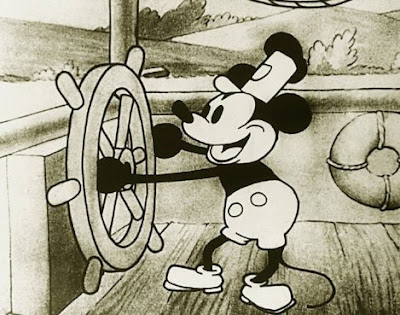

But the real cherry on top is that after all these years, time has finally come for Disney. Next year, on January 1st 2024, Mickey Mouse, as he appears in Steamboat Willie, enters the public domain. Get ready to slap this fella on some T-shirts, people! Oh, but don't give him gloves. Or pupils. Those weren't invented yet.

|

| Mickey, gleefully sailing into the Public Domain. |

Public pressure caught up with the Disney company in the internet age. As the story of how they and the likes of Sonny Bono (Team Cher and Cher only for life!) destroyed our legal right to use old stories started to circulate online, Disney amended their stance so that they no longer are putting forward bills to stop the slow roll-out of works entering the public domain at the end of each calendar year. Instead, they're simply arguing that they hold copyright to later versions of the character, until cartoons that feature aspects like his gloves do enter the public domain. But whatever. Screw it. We're still getting the Mouse and whole boat.

I'm perfectly happy to watch someone make a movie about Mickey and Minnie's adventures as pirates on the Mississippi River. Or that Winnie the Pooh horror movie team can make one about him strapping victims to a torture rack made from the steamboat wheel. Or maybe we'll get a crime drama about how Mickey's father died during a fire in Pete's glove factory and now he's now on a quest to destroy all gloves. Distributed widely. All without Disney's approval. I can hardly wait.

We spent years stuck in the past but, finally, we're not in Kansas anymore.