|

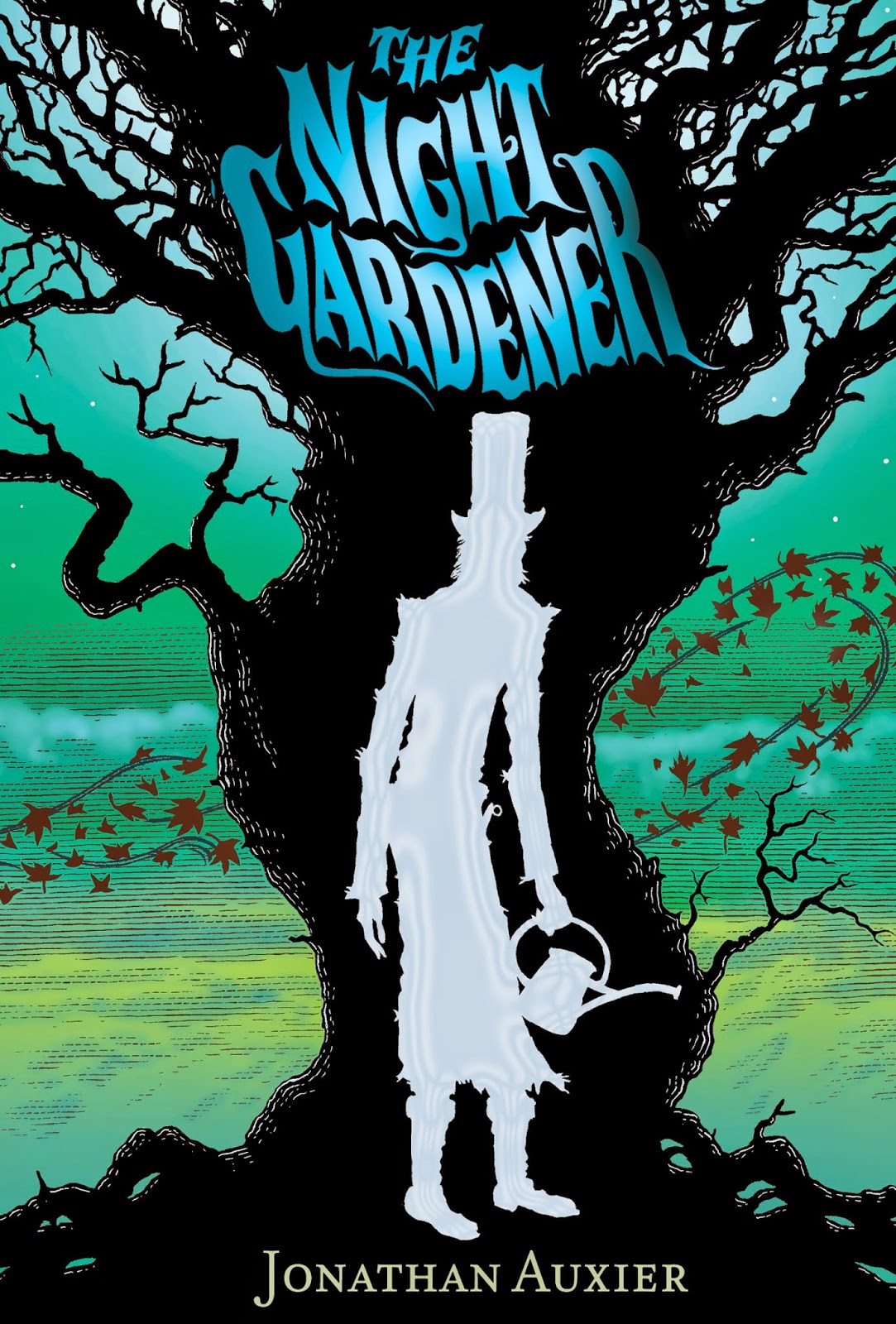

| The Night Gardener |

But the longer they stay in the house, the clearer it becomes that every bystander who warned them to avoid the road into the Sourwoods might have been right to be superstitious. Illness lurks inside the house and a stranger prowls the grounds at night.

And then there is the tree. The great, terrible, black tree, growing beside the manor house...

What makes it so good:

So I have a bit of a history with this book! This review is probably going to be part review, part self-indulgent reveling in the past. You have been warned!

I had just started attending classes at Chatham University. I was living the dream, studying what I'd wanted to since grade school. Creative writing. Better than that, creative writing, with my primary genre focus being writing for children and young adults.

One of my foundation classes was therefor in Children's Literature, taught by Jonathan Auxier. You might recognize him as the gent whose name is directly below the night gardener's feet on the book's cover. At the time, this book was a year and a half away from release and Jonathan was knee-deep in revisions. And that, friends, is very deep. He's a tall man.

As a result, The Night Gardener was one of the first books I've ever had any insight into the "journey" of. As one of his students, we certainly weren't the ones giving critique and feedback on it in its infancy. We heard little snippets. What it was like working with an editor on a novel-in-progress, what writing a duel point-of-view novel meant. How important it was to start your second book as soon as possible after the release of your first.

And our reading list, it turns out, consisted of numerous titles that eventually made it into the author's note at the end of The Night Gardener - books like Something Wicked this way Comes and The Secret Garden. *coughI think someone might have had ulterior motives for making us read and discuss those bookscough*

But that's actually one of the reasons I wanted to cover this book now! On the heels of the earlier discussion of books that are "derived" from earlier sources rather than "derivative" of them, I thought it would be fun to discuss books that are very upfront about their literary influences and which can only be described as reveling in those connections. The Night Gardener is among them.

I recently discussed with someone whether or not Gardener could be considered historical fiction. Certainly the history and the setting play into the richness of the story. And even the more fantastical, horror elements harken back to the Victoria era. As Auxier says in his own author's note, the era was one of rapid scientific discovery, but also fascination with the spiritual and occult, something The Night Gardener plays with.

But overall, I couldn't conclude that it was historical fiction. Usually the genre is interested in teaching something about the past as one of it's primary goals, and I never got the sense The Night Gardener held this as its motive. This book isn't trying to teach the reader something about the "facts" of the Victorian era - it's aiming to teach you about it's stories.

But overall, I couldn't conclude that it was historical fiction. Usually the genre is interested in teaching something about the past as one of it's primary goals, and I never got the sense The Night Gardener held this as its motive. This book isn't trying to teach the reader something about the "facts" of the Victorian era - it's aiming to teach you about it's stories.

Among the characters are two story-tellers. First, the old Hester Kettle, a vagabond story teller who always seems to know more than she should, and second, one of novel's heroes, Molly. Only fourteen, Molly is still learning the difference between a story and a lie.

That a story this steeped in literature and the history of children's books also comes with a satisfying element of horror meant that I loved the book. And this isn't bias speaking, either! This isn't Jonathan's first book, but in my humble opinion, it is his best. All the elements just came together beautifully - the horror, the old fashioned prose, the characters. It's all there. It's funny, touching and terrifying. I highly recommend it.

What might make it better:

This is a very, very long and very, very verbose children's book.

For me, it works. The reading level isn't easy, and while it's a quick read, it isn't as quick as some comparable books. To give an idea, Neil Gaiman is well known for his children's scary stories. Coraline, definitely a Middle Grade book, is only 30,000 words. The Graveyard Book sort of straddles the line between Middle Grade and Young Adult, and is around 67,000. Definitely on the longer end of Middle Grade, but okay for the anticipated audience. The Night Gardener clocks in at over 79,000 words. It also straddles the line between YA and MG, but I think it's pretty clear that for some kids, that's a lot of reading.

Tonally, it still reads like a Middle Grade book rather than YA, but with it's dark subject matter and hefty sentences, it's not going to be a breeze for all children. Still, I think it does fill a niche that a lot of people worry about in children's literature. I hear plenty of people who love books bemoan that we no longer get books for children like The Hobbit. They usually say something like this:

Tonally, it still reads like a Middle Grade book rather than YA, but with it's dark subject matter and hefty sentences, it's not going to be a breeze for all children. Still, I think it does fill a niche that a lot of people worry about in children's literature. I hear plenty of people who love books bemoan that we no longer get books for children like The Hobbit. They usually say something like this:

"When I was eleven, I read all of Tolkien's Lord of the Rings books! I wanted to be challenged. These kids books today, they just aren't challenging. Have you read Twilight? Way too easy! Such bad writing."

First, I'm not saying that The Night Gardener necessarily bares a lot in common with The Hobbit or Twilight. It's just that most of my friends are sci-fi/fantasy nerds and they all somehow think it makes sense to compare epic fantasy to paranormal romance (it doesn't). I thought it had more in common with older books - ones like those by Robert Louis Stevenson and Charles Dickens which, again, people wished children read. Or were prepared to read. This is exactly the type of book that introduces the wonder and creepiness of the Victorian era to young readers.

Second, I don't personally believe that a book being an "easy" read or not is the same as whether or not it's good or bad. Charlotte's Web is a very easy book and its completely brilliant. But there is something to be said for a book that gets its beauty from its use of complex language. To give you an idea of what The Night Gardener challenges its reader with, I spent a lot of the book trying to remember what a dumbwaiter is.

|

| Behold the dumbwaiter! |

And in general, do read it. And think of the wonderful tradition of stories that it places itself a part of. Think of the history of books we draw from, and how we all derive something from that history.